The

ability to create stories is an innate human trait. It is this evolutionary

predisposition that has allowed humanity to have shared experiences, be it for

education, entertainment or for self-preservation. Storytelling

includes many aspects including religious and secular teaching, philosophy, gossip,

poetry, myths, traditions, propaganda, scientific writings, speeches, news,

articles, advertisements, plays, movies, television stories, songs, and also sadly

lying. We consume stories voraciously through various forms and media.

Storytellers,

especially the good ones, can enter into our imagination and interact with our

deepest human emotions. They can inspire us to strive for greatness or motivate

us to do great evil. They can make us happy, angry or sad. They can make us

laugh or cry. Storytelling and human emotion are closely linked, starting at

infancy, they strongly influence every aspect of our life.

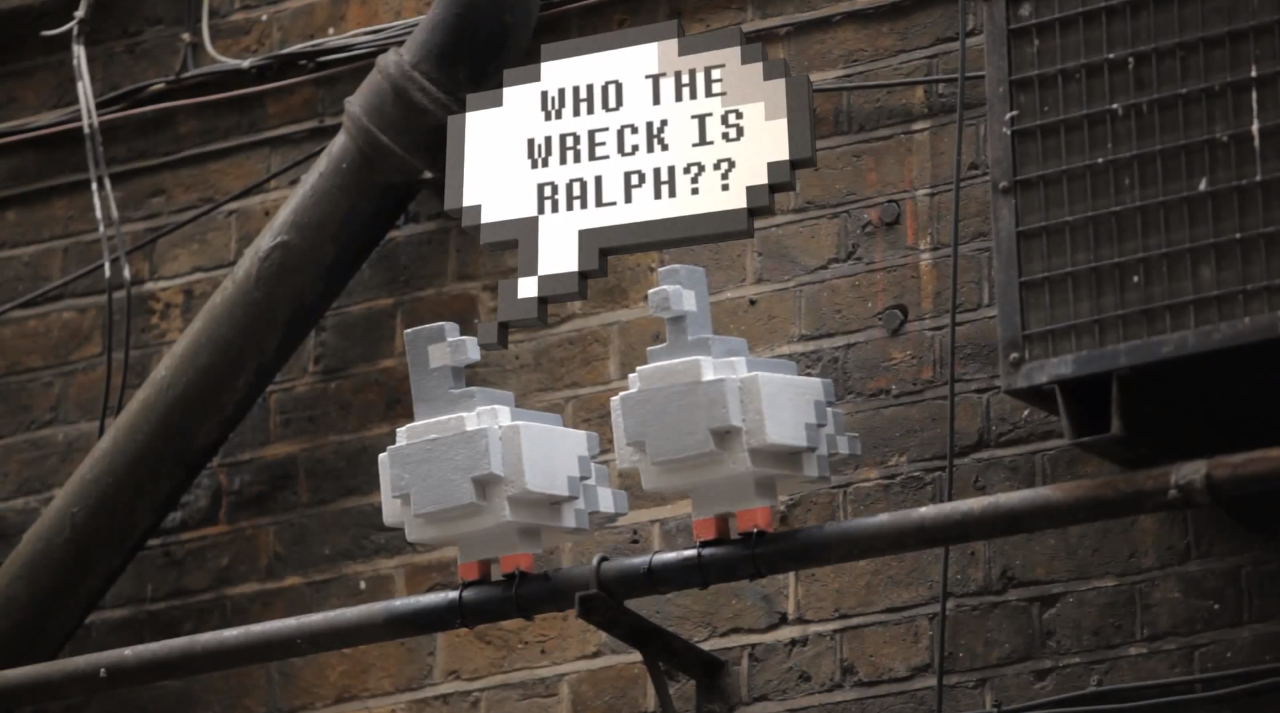

Computer

games are a relatively new media and there are storytelling elements contained

within. Using computer games we can immerse ourselves in these stories and

worlds, interacting with the storytelling. We can become active participants

rather than passive observers. However whilst it is possible to tell stories in

computer games, the nature of interactivity raises the question of whether they

do so effectively. As games have grown increasingly sophisticated, so too has

the methodology and purpose of their narrative. However computer games are set

by rules; your character has a limited set of behaviours he can follow due to

the nature of programming. The restrictions are in place due to computational

powers but also due to the need to drive the story forward. Often the story in

computer games is superfluous, often based around the game play mechanics and

characters; a branching database of options and permutations on the decisions

made within the game. This is in contrast to something like Dungeons and

Dragons, where the Games Master (using the rulebook) can create scenarios ad

infinitum.

To

truly tell a good story in games the games mechanics have to be built in

conjunction with the scenarios; a marriage of narrative and gameplay. Stories

are fixed designed experiences whilst computer games let players change things,

even when it’s simply walking across an island like in Dear Esther. Eschewing

traditional gameplay mechanics this interactive world immerses and engages the

player through the use of amazing visuals, beautiful audio and wonderful prose.

What I have learnt through game based learning is that neither the game nor the

story contained within, are that important but rather it is how you use

the game.

As

a teacher we can use games to provide children with a deep emotional and

exciting experience. We do not have to use the whole game but sections. Whilst

the narrative contained within the game itself may not be that exciting,

children with their innate skills to weave stories may make an infinitely more

nuanced story. Computer games allow the pupils to become stimulated in the same

way text and film can, but have a benefit over these other media in that they

can interact with these worlds. If we want to go left we can, the world is

literally our oyster, full of endless possibilities and the children know this.

It taps into their innate ability to tell stories but provides a rich context

for doing so. This is not new, games have been used as a contextual hub for

learning in many schools I know across the UK and there are many individuals

who have done sterling work in the area, including Consolarium, Tim Rylands, Ollie

Bray and the Redbridge Games Network, and many many others. However in Cambodia,

where much of the educated people were wiped out in Year Zero by the Khmer

Rouge this is a revelation. Computer games are still seen as a childish tool or

as quick timewasters but I have used many games as a stimulus for writing. Here

are the lists of games we have used and how we have used them: