The term 'walking simulator' is used to describe a genre of games where a person is asked to explore a setting but there are little to no action buttons to press. As a result many gamers speak of 'Walking Simulators' in a derogatory way claiming that they are not in fact ‘games.’ It may seem like semantics but how we label the genre implies that all you do is walk from one side to the other in a guided tour fashion. However there is more to these types of games than belies the title assigned to them.

Walking simulators have gone through a bit of a journey themselves, gaining prominence with Dear Esther and Proteus, which initiated the debate on whether they were games or not. The games did well, but some people asked for a refund from Steam, an online gaming marketplace, claiming there was nothing to do and that these were not ‘real’ games. Since then, games like Firewatch, Edith Finch, Gone Home and The Vanishing of Ethan Carter have raised the profile and respectability of the genre amongst many ‘hardcore’ gamers but there is still a stigma attached to this genre for many.

In these games, the story is told by journeying through the world and finding elements within the world rather than through traditional storytelling narrative and the players input is often minimal. However I find that they are incredible experiences that reward exploration and discovery to understand the bigger narrative. Often by finding diary entries, audio files and environmental clues you get to understand the mystery box structure of the narrative, told slowly and carefully throughout the game.

This genres provides immersive worlds to engage and interact with. In the same way that art has many different forms so do computer games. I recently played through Control, Uncharted: The Lost Legacy and Call of Cthulhu and whilst I loved those games sometimes it is great to try something more calm, cerebral and emotional.

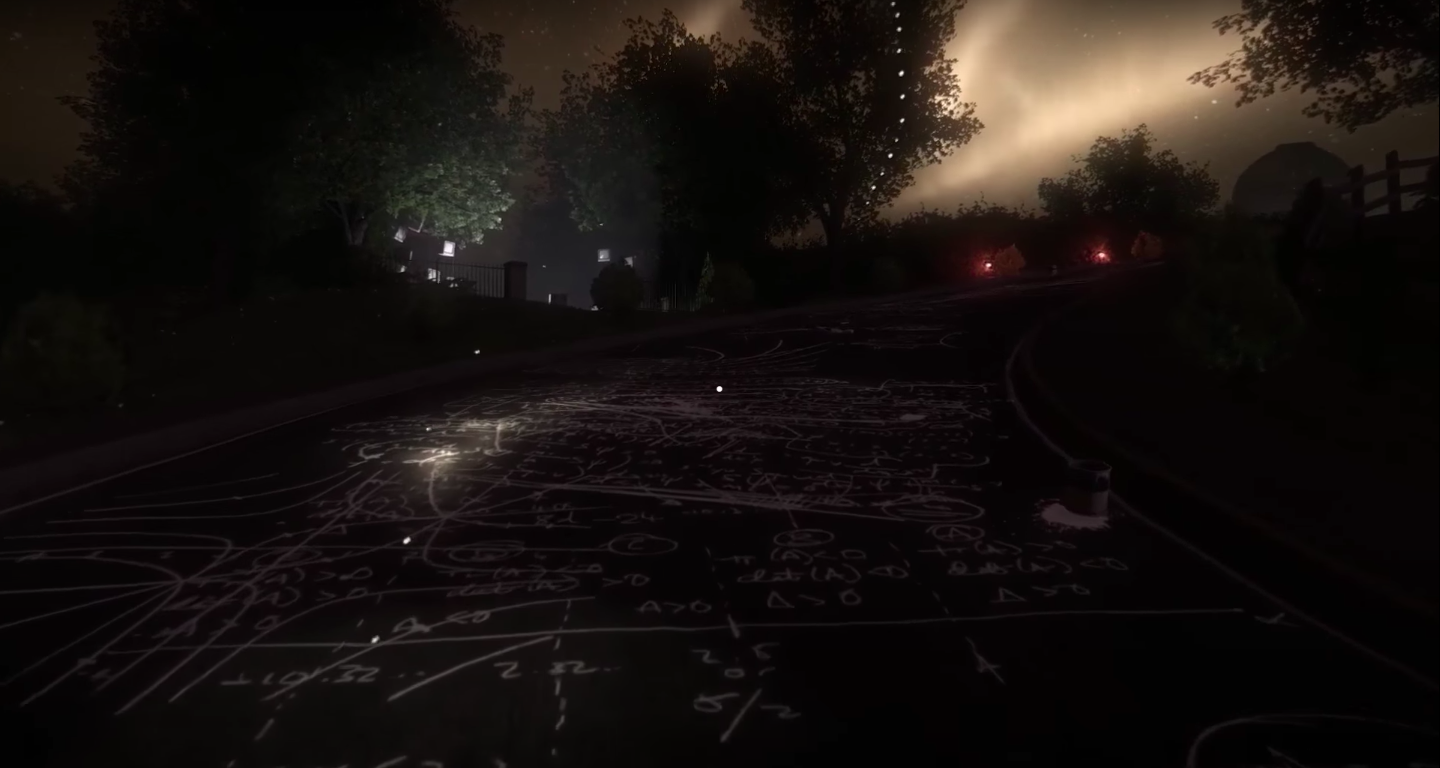

During the first few weeks of Covid lockdown I recently revisited The Chinese Room’s ‘Everybody's Gone To The Rapture’ and it struck me again how wonderful and immersive this ‘walking simulator’ is yet also prescient. I won't spoil it for people who haven't played it but the game sets you in an English village where some catastrophe has occurred and you are the lone survivor. You spend the 4 or so hours of the game exploring the silent and empty village finding orbs of light that relay events which occurred in the village, like some voyeur. It feels almost like survivor’s remorse in that you hear peoples pains, anguish and worries. There are some profound moments in the game that will stick with me forever, more deeply embedded than some forms of media because I was the active agent that made these things occur. The way the narrative is presented eschews the typical linear chronological route and instead you have to piece things together, almost like a David Mitchell or Haruki Murakami novel, which is quite an achievement.

During the weirdness that is Covid, the sight of an isolated empty English village took on a bigger significance as I had experienced it virtually first. The connection between myself and the game were even more deeply bound than when i played the game initially as I had the ludonarrative connection… something similar was happening around me. Okay, not the rapture but lockdown when streets were empty, shops were shut and people were just not around. This game, and many others like it, are examples of how an interactive narrative can deliver an emotional pay-off like no other medium.

'Walking simulators' are a wonderful genre of video games and they encourage us to immerse ourselves in new worlds and scenarios. They are rather passive and sometimes that is what I look for in gaming, it’s a bit of a change from the norm. Along with much of the world I was inside but with video games I went on some incredible journeys.