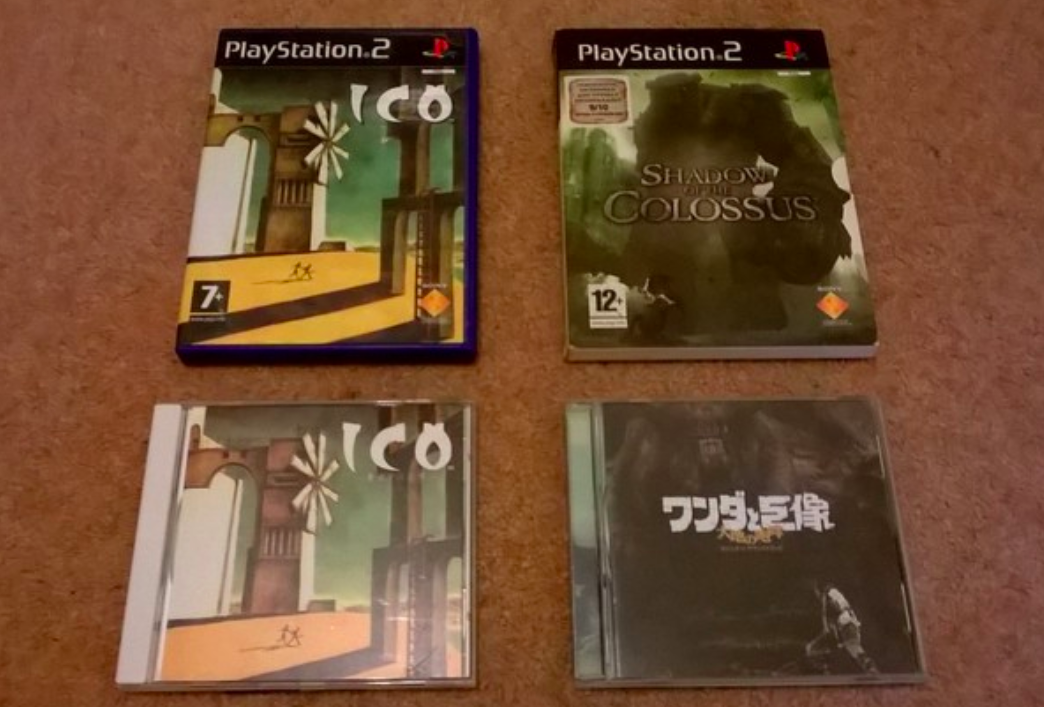

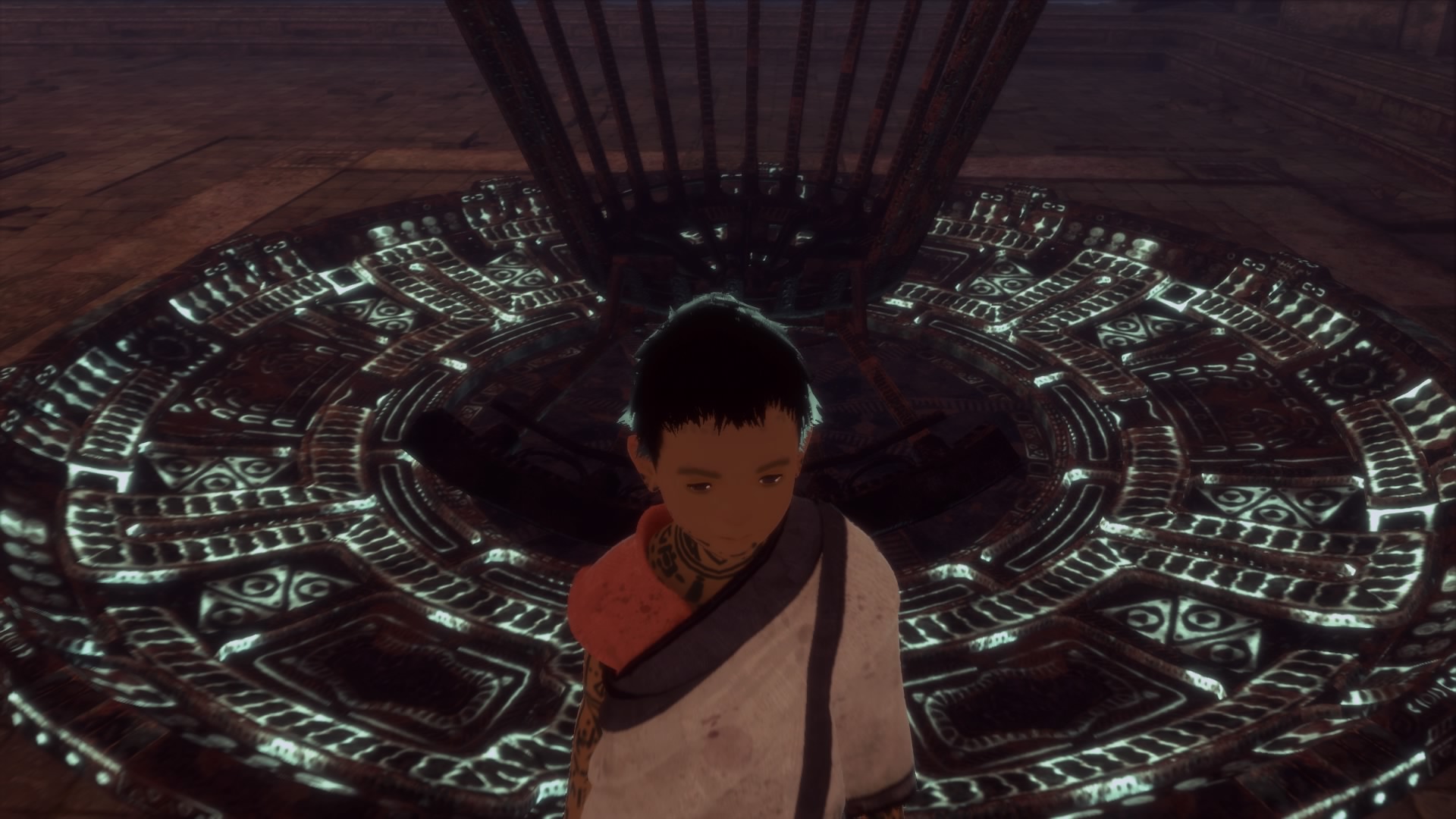

Paul Grimault's The King and the Mockingbird endured a tumultuous production, finally gracing screens in its completed form in 1979 after decades of legal battles and studio interference. While I had never before experienced this film, its formidable reputation preceded it. Its influence has echoed through animation history, most notably in the works of Studio Ghibli's luminaries, Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, both of whom readily acknowledge it as a key inspiration. Intriguingly, its tendrils of inspiration have also stretched into the realm of video games, particularly the evocative and emotionally resonant experience of Fumito Ueda's Ico, which, in turn, provided a spark for Hidetaka Miyazaki's Dark Souls series.

The narrative, a loose adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen's The Shepherdess and the Chimney Sweep, unfolds in the tyrannical kingdom of Takicardia, ruled by the grotesque and insecure King Charles V + III = VIII = XVI. His towering, multi-layered palace, which serves as a character in itself, sets the stage for a whimsical yet poignant tale of forbidden love between a charming chimney sweep and a beautiful shepherdess, both escaping from their painted portraits. Their flight from the King's clutches, aided by the sardonic and wise Mockingbird, who also acts as a raconteur and narrator, takes them through the bizarre and often menacing levels of the palace and the sprawling city below.

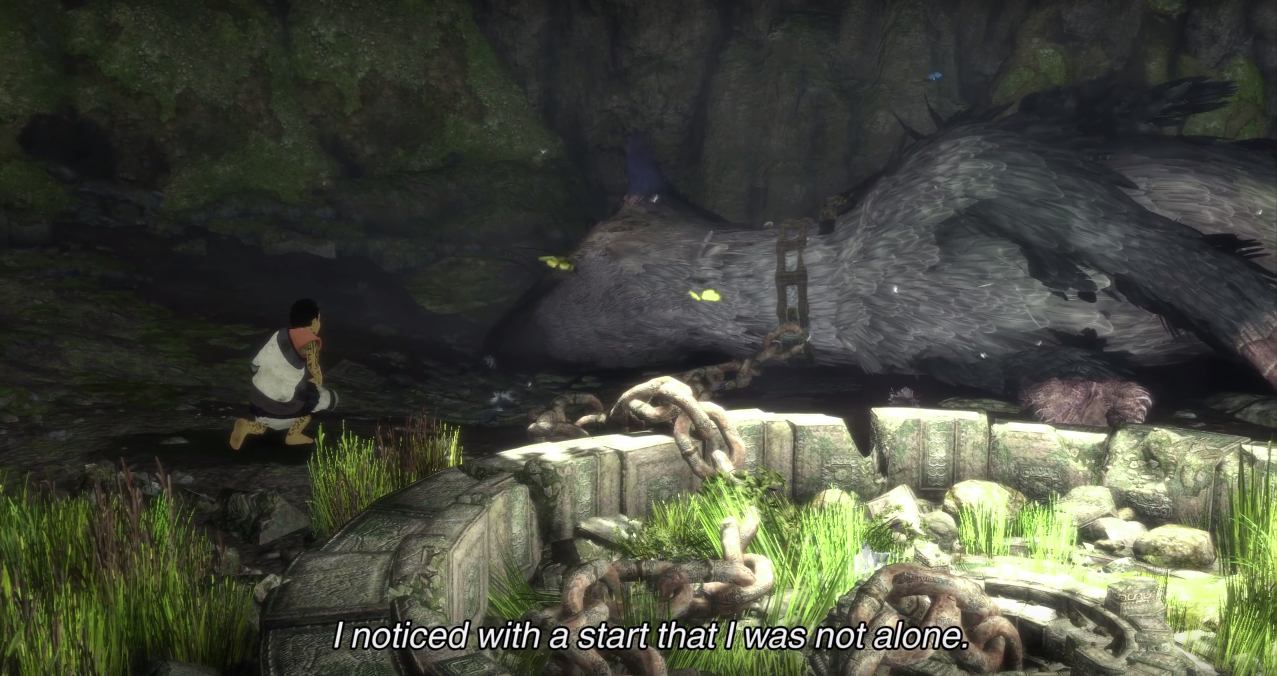

What makes The King and the Mockingbird so enduring is its unique blend of visual poetry and thematic depth. The animation is fluid and expressive, shifting seamlessly between moments of slapstick comedy and breathtaking beauty. The architectural designs, inspired by the works of Gérard Trignac mixed with the Parisian and Venetian influences of artists like de Chirico and Magritte, create a sense of otherworldly grandeur and underlying unease. This very atmosphere, where the familiar is twisted into something dreamlike and slightly unsettling, finds a clear echo in the world of Ico. The connection is not in direct plot points but in the shared atmosphere and visual language. There are many parallels including:

the towering architecture acting as a character; King Charles's colossal palace dominating Takicardia and the enigmatic castle in Ico serving as a central, almost sentient location,

both labyrinthine structures emphasizing the protagonists' vulnerability,

the unlikely partnership between the chimney sweep and shepherdess against the King, reflecting Ico and Yorda's reliance on each other for survival,

a shared sense of melancholy and isolation permeating both works, highlighting the protagonists' outcast status,

a minimalist narrative style favoring visual storytelling and environmental clues over heavy exposition and the pervasive surrealism and dreamlike quality present in Takicardia's illogical elements and the abstract nature of Ico’s castle.

Overall, I thought that The King and the Mockingbird was a triumph of animation. It is a film that defies easy categorization and I can see why it continues to inspire generations of artists, even those who do not have nostalgia attached to it; it's a shimmering, surreal dreamscape wended with poetic dialogue and striking visuals that lingers long after the final frame. It is filled with both wonder and a touch of melancholy which lasts long after the film has ended. It was a wonderful experience and stands as a testament to artistic vision triumphing over adversity.